So finally you’re testing your frontend JavaScript code? Great! The more you write tests, the more confident you are with your code… but how much precisely? That’s where code coverage might help.

The idea behind code coverage is to record which parts of your code (functions, statements, conditionals and so on) have been executed by your test suite, to compute metrics out of these data and usually to provide tools for navigating and inspecting them.

Not a lot of frontend developers I know actually test their frontend code, and I can barely imagine how many of them have ever setup code coverage… Mostly because there are not many frontend-oriented tools in this area I guess.

Actually I’ve only found one which provides an adapter for Mocha and actually works…

Drinking game for web devs:

— Shay Friedman (@ironshay) August 22, 2013

(1) Think of a noun

(2) Google "<noun>.js"

(3) If a library with that name exists - drink

Blanket.js is an easy to install, easy to configure, and easy to use JavaScript code coverage library that works both in-browser and with nodejs.

Its use is dead easy, adding Blanket support to your Mocha test suite is just matter of adding this simple line to your HTML test file:

<script src="vendor/blanket.js"

data-cover-adapter="vendor/mocha-blanket.js"></script>

Source files: blanket.js, mocha-blanket.js

As an example, let’s reuse the silly Cow example we used in a previous episode:

// cow.js

(function(exports) {

"use strict";

function Cow(name) {

this.name = name || "Anon cow";

}

exports.Cow = Cow;

Cow.prototype = {

greets: function(target) {

if (!target)

throw new Error("missing target");

return this.name + " greets " + target;

}

};

})(this);

And its test suite, powered by Mocha and Chai:

var expect = chai.expect;

describe("Cow", function() {

describe("constructor", function() {

it("should have a default name", function() {

var cow = new Cow();

expect(cow.name).to.equal("Anon cow");

});

it("should set cow's name if provided", function() {

var cow = new Cow("Kate");

expect(cow.name).to.equal("Kate");

});

});

describe("#greets", function() {

it("should greet passed target", function() {

var greetings = (new Cow("Kate")).greets("Baby");

expect(greetings).to.equal("Kate greets Baby");

});

});

});

Let’s create the HTML test file for it, featuring Blanket and its adapter for Mocha:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Test</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" media="all" href="vendor/mocha.css">

</head>

<body>

<div id="mocha"></div>

<div id="messages"></div>

<div id="fixtures"></div>

<script src="vendor/mocha.js"></script>

<script src="vendor/chai.js"></script>

<script src="vendor/blanket.js"

data-cover-adapter="vendor/mocha-blanket.js"></script>

<script>mocha.setup('bdd');</script>

<script src="cow.js" data-cover></script>

<script src="cow_test.js"></script>

<script>mocha.run();</script>

</body>

</html>

Notes:

- Notice the

data-coverattribute we added to the script tag loading the source of our library; - The HTML test file must be served over HTTP for the adapter to be loaded.

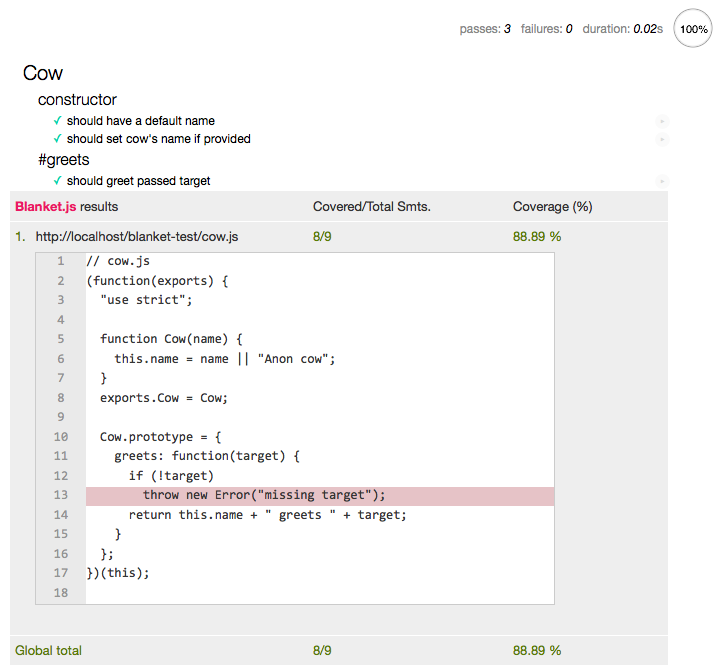

Running the tests now gives us something like this:

As you can see, the report at the bottom highlights that we haven’t actually tested the case where an error is raised in case a target name is missing. We’ve been informed of that, nothing more, nothing less. We simply know we’re missing a test here. Isn’t this cool? I think so!

Just remember that code coverage will only bring you numbers and raw information, not actual proofs that the whole of your code logic has been actually covered. If you ask me, the best inputs you can get about your code logic and implementation ever are the ones issued out of pair programming sessions and code reviews — but that’s another story.

So is code coverage silver bullet? No. Is it useful? Definitely. Happy testing!

This post has been published more than 11 years ago, it may

be obsolete by now.

This post has been published more than 11 years ago, it may

be obsolete by now.